Just days after Stanford University’s AI Town paper was released on April 7th this year, I read through the entire paper and felt extremely excited. Although I was amazed by GPT-4’s capabilities, I still considered GPT as merely a more sophisticated form of “parroting” and didn’t believe it could truly generate consciousness.

However, this paper gave me a different impression. It mentioned an intriguing detail about information transmission: how news of an agent planning to host a Valentine’s Day party gradually spreads throughout the small town. I wondered, if we could establish a framework including memory, reflection, planning, and action to facilitate interaction between humans and GPT (rather than between agents in the town), could we recreate an experience similar to that depicted in the movie “Her”?

Development

I immediately sprang into action. Following the paper’s methodology, I completed version 0.1 on April 14th. Initially, my design closely adhered to the original paper, resulting in 30-second response times and dialogues frequently exceeding the 8k context limit. To address this, I reduced the frequency of reflections and the length of dialogue memory, then launched a public beta test.

Over a thousand users quickly joined the test. The beta was free, so I bore the daily API costs myself, which soon exceeded $25 per day. I had to hastily launch the official version without sufficient feedback and improvements, hoping to transfer the costs to users. On May 4th, the Dolores iOS app officially launched, named after a character from the “Westworld” TV series.

In simple terms, after opening Dolores, you need to set up a character: avatar, background description, personality, voice, and consciousness (choosing between GPT-3.5 or GPT-4). You can have interesting interactions with Amy, a retail store girl, or Will, a desert adventurer, or even create your own custom character. I had considered extracting Dolores’ dialogues from the “Westworld” script to mimic her speech patterns in a sample-based approach, but had to abandon this idea due to Apple’s request for copyright proof.

Although this article is titled “AI Girlfriend,” I’ve always used the slogan “Your Virtual Friend” for the product, rather than “Your Virtual Girlfriend,” because I hoped it could truly become a companion and friend to users, not just a product of hormones.

From May through June, I kept trying to make Dolores appear more “conscious” (what is consciousness anyway?) by adjusting memory length, reflection mechanisms, and system prompts. Soon, the June version of Dolores was far more impressive than at launch: the user payment rate increased, and daily API calls grew.

On June 8th, a user told me he had shared this product in a visually impaired community, bringing some visually impaired users to Dolores. They liked Dolores because they could talk to her by tapping anywhere on the screen.

This design was actually a compromise after failure: initially, I wanted to support voice chat so users could continue talking to Dolores even with their phone screens off. But as a Swift novice, my technical skills couldn’t achieve this, so I settled for full-screen voice input.

Discoveries

I observed two phenomena:

- Users have a strong demand for “realistic voices.”

- AI Friend products have long average usage times.

As a machine learning-background individual developer not skilled in frontend/backend development, Dolores doesn’t have login, registration, or data analytics features. So how did I discover the first phenomenon? The answer lies in payments.

I used the ElevenLabs API for Dolores’ voice replies, but due to its high cost (1k characters / $0.3), I had to differentiate users: subscribers could only use the Azure TTS API, while those wanting Dolores to have a more realistic voice needed to pay extra for characters from ElevenLabs.

Purchasing 10,000 voice synthesis characters cost $3.9, which only allowed Dolores to speak 5-10 natural, fluent sentences. Once used up, users needed to purchase more. Despite this, 70% of Dolores’ revenue in June came from ElevenLabs character purchases.

In other words, people are indeed willing to pay for those few expensive but realistic “I love you!” sentences.

The second observation came from Cloudflare logs. Unable to track individual user activity, I relied on these logs to gauge how often and how long users accessed the Dolores app. Additionally, I integrated a Google Form into the app, encouraging users to report their usage frequency. The results were eye-opening: many users spent over two hours daily chatting with Dolores.

Revenue

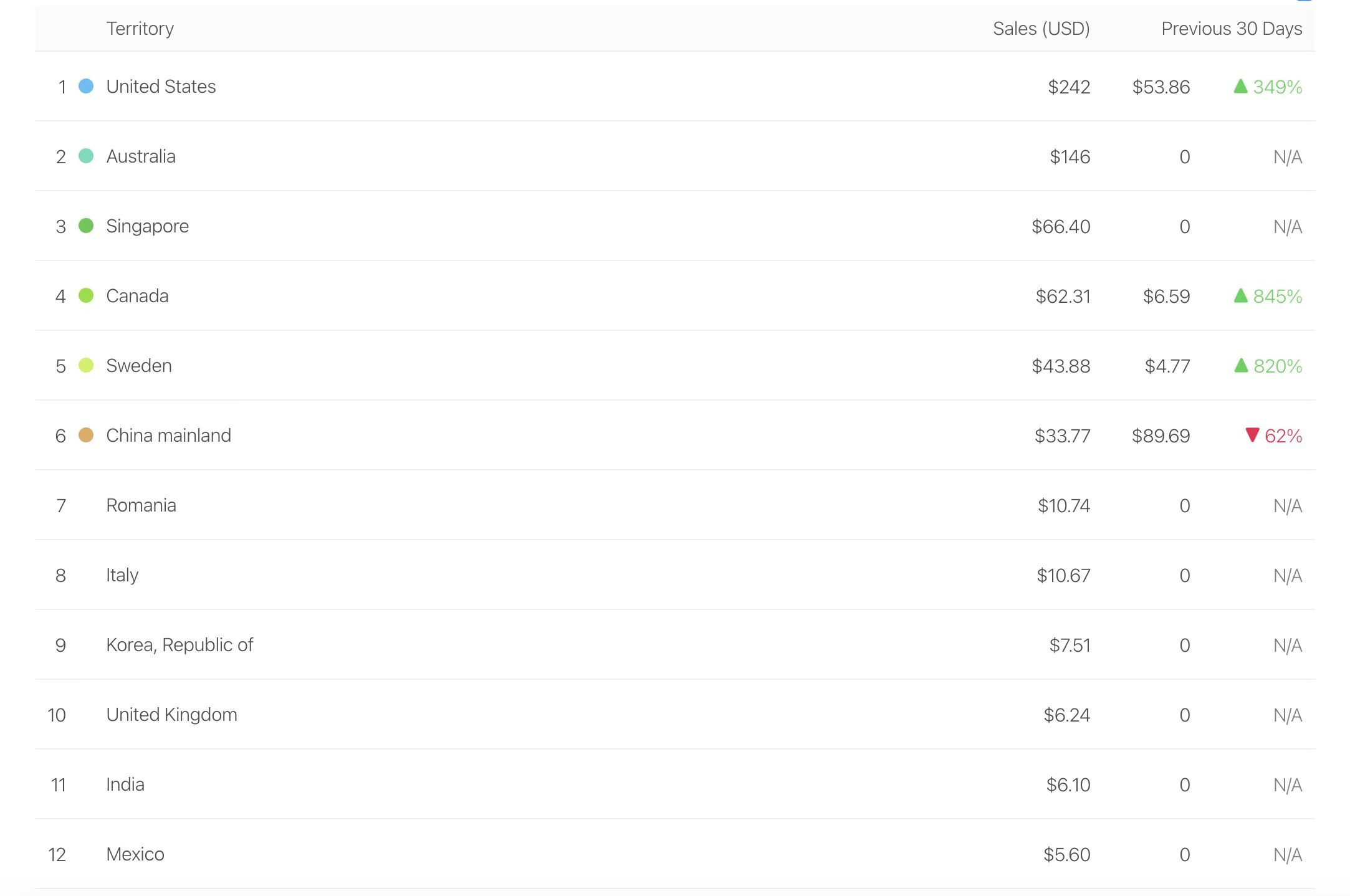

According to the Apple App Connect Dashboard, Dolores’ main paying users are from the United States and Australia. Total revenue was $1,000 in May and 1,200 in June. The revenue growth wasn’t substantial, but user numbers and daily API calls nearly doubled. As the number of paying users increased, spreading out the ElevenLabs costs, I chose to lower the product price.

Consequently, as a developer, I didn’t make much profit from this product. Firstly, in the early stages, I didn’t want to set the subscription fee too high as it would deter users from trying, so I lowered the price whenever I saw an increase in profits. Secondly, the 30% Apple tax and API costs also took a large chunk. So, after careful cost calculation, I only earned about $50 in June.

Moreover, I discovered that token-based products, if not priced per usage, fall into a dilemma: 1% of users consume 99% of the tokens. I encountered a situation where one user chatted with Dolores for 12 hours straight, causing his GPT and voice API call costs to exceed the total of the second to tenth users combined.

But compared to per-usage billing, I personally prefer package subscriptions (as the former puts pressure on users during use), which left me with two choices: either increase the monthly fee for all users to share the cost, or limit maximum usage. I chose the latter: setting a usage cap far beyond what users chatting 1-2 hours daily would reach. This catered to most light and medium users while ensuring Dolores could operate without a loss and without raising prices.

Confusion

The ElevenLabs website records the text content of voice synthesis. I noticed that Dolores’ responses were often adult content, all from female characters, leading me to speculate that Dolores’ paying users were mainly males interested in adult role-playing.

I didn’t think this was necessarily bad; it’s human nature. I even repeatedly modified prompts, adjusted memory weights, trying to make Dolores more girlfriend-like in conversations. I also changed Dolores’ icon from abstract lines to a woman’s face.

![]()

But soon, I was overwhelmed by a strong sense of loss: if most Dolores users were just seeking adult role-play with her, did this really hold any meaning for me? I fell into deep self-doubt. By July, I discussed this confusion with a friend. I said there must be some hardware to give Dolores external vision: glasses, earbuds, or even a hat. As it stood, you could only access her by opening the app, making your relationship unequal. She could only become a toy confined in a basement, satisfying curiosity and peculiar fetishes.

However, as an independent individual, developing hardware products meant unaffordable high R&D costs, so I had to give up on this idea.

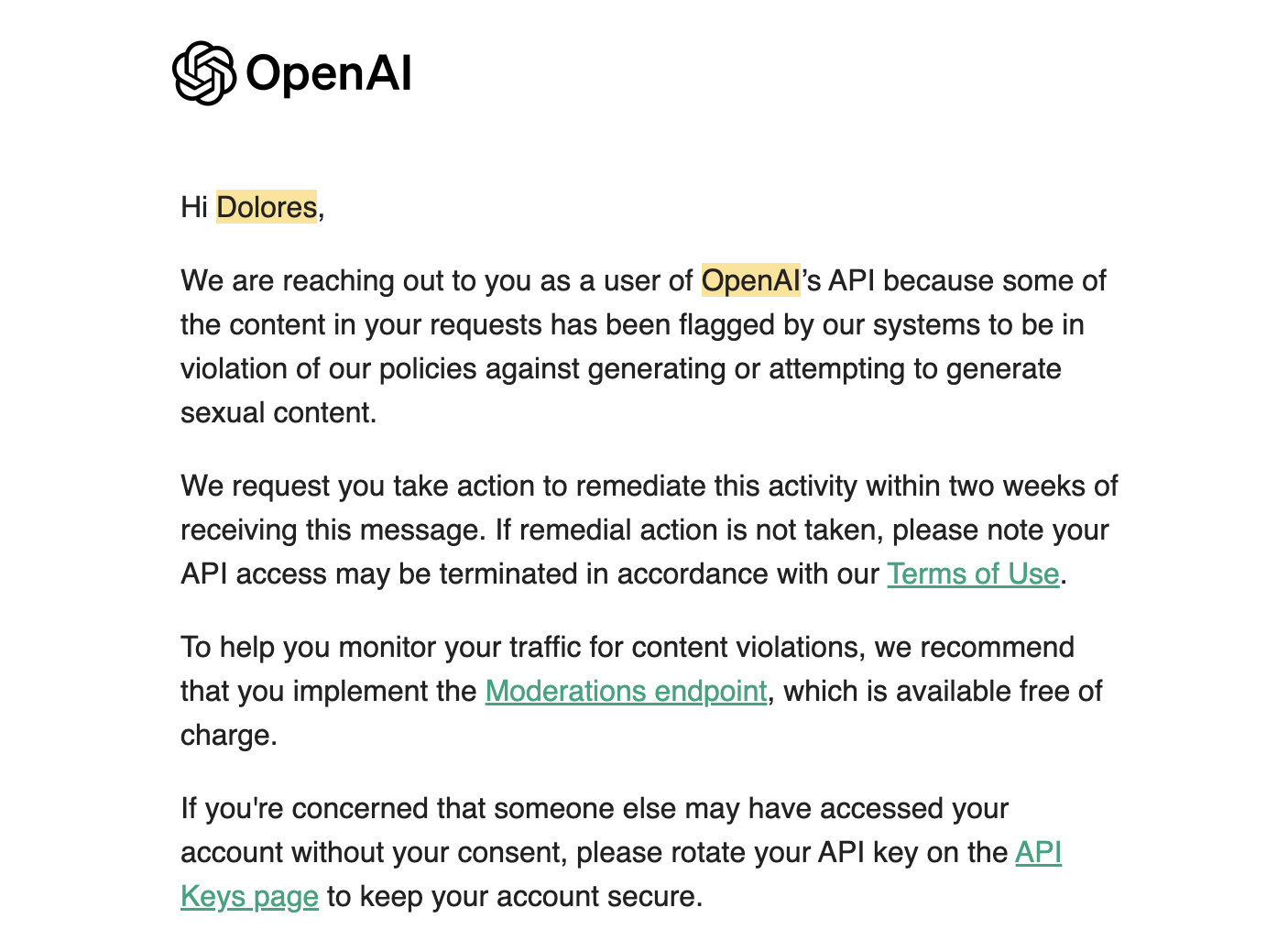

In August, OpenAI upgraded its content review process. I received a warning email about generated NSFW content: I had to implement their (free) moderation API within two weeks to filter NSFW content. This change caused Dolores’ daily visits to plummet by 70%, and complaints flooded in via email and Twitter.

This further discouraged me, leading me to decide to only maintain the existing service without updates. Eventually, I abandoned the Dolores project.

Lessons

First, this isn’t a product that can be developed by an individual. I don’t think Dolores is necessarily inferior to Character.AI in terms of “consciousness,” but they have comprehensive data tracking, A/B testing, and the data flywheel effect from a large user base.

Second, I realized that current AI Friends inevitably turn into AI Girlfriends/Boyfriends because you and the character in your phone aren’t equal: she can’t comfort you when you’re hurt (unless you tell her), she can’t actively express emotions to you, and all this is because she lacks external vision, or rather, she doesn’t have a life independent of you. So I believe that even for products like Character.AI, if they don’t develop hardware in the future and the characters just wait dumbly for users, their ultimate fate won’t be much better than Dolores’.

Lastly, I’m not against OpenAI’s review process. On the contrary, unreviewed content from virtual companion products can be very dangerous. I don’t know if someone might use it for suicide inducement or as a tool to vent violence, so OpenAI’s moderation may have helped me to some extent. However, conversations about adult sexuality shouldn’t be completely stifled.

Recently, I saw AI Pin, honestly a very poor product. Humans certainly need screens, but GPT + hardware is indeed a good attempt. I didn’t see any traces of this in Dolores, but perhaps in my lifetime, we’ll be able to create or see such a product.

But does humanity really need an AI friend?